“… a woman alone at the mirror with her reflection instead of – her dreams? her memories? her soul?”

A PERFORMANCE POEM

HAJJ

WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY

LEE BREUER

PREMIERE

The Public Theater, April, 1983

A NEW YORK SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL/MABOU MINES PRODUCTION PRESENTED BY JOSEPH PAPP

A PERFORMANCE POEM WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY

LEE BREUER

PERFORMED BY

RUTH MALECZECH

SET AND LIGHTING BY

JULIE ARCHER

VIDEO BY

CRAIG JONES

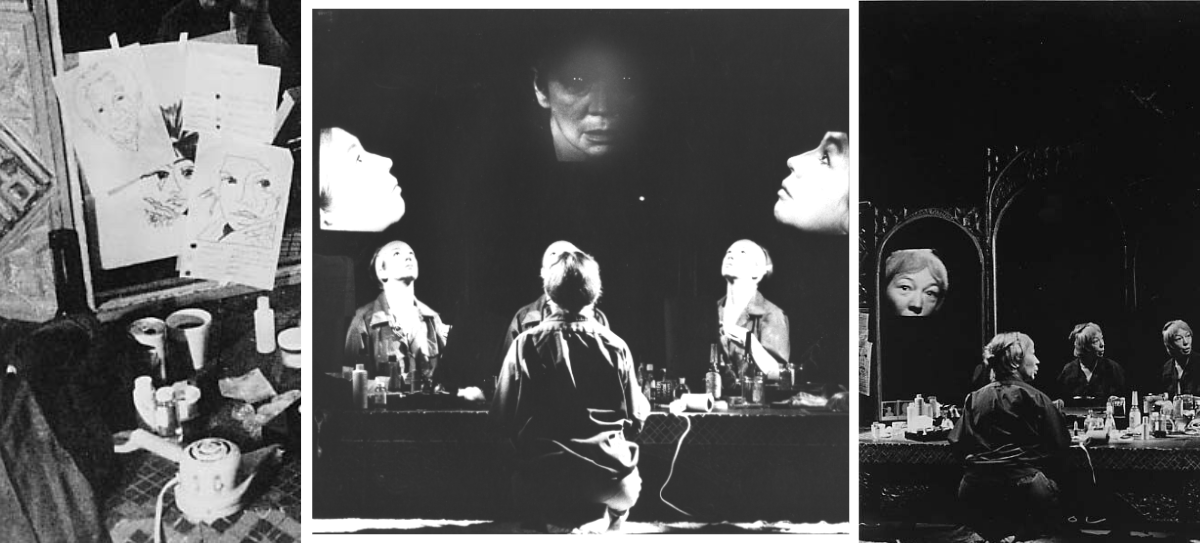

“The actress Maleczech sits down at a vanity table, her back to the audience. She faces a triptych of tall, ornately framed mirrors and begins to apply an elaborate makeup. When she reaches for a hairpiece, a video monitor suddenly reveals itself behind one of the mirrors and a closed-circuit camera zooms in on the hairpiece.

As she continues putting on her makeup, monitors behind the other two mirrors flicker on, picking up similarly specific images – a necklace, the smoke from her cigarette. The actress murmurs the text (picked up by a high-powered body mike) as the screen images float alongside her reflection in the mirror, and these are soon joined by another layer of imagery. Filmed sequences showing a child on the lap of an old man and a truck driving through a barren landscape are superimposed on closed-circuit images of Maleczech’s face or objects on the makeup table. As suddenly and magically as they appear, the video pictures periodically drop out altogether, leaving a woman alone at the mirror with her reflection instead of – her dreams? her memories? her soul? …

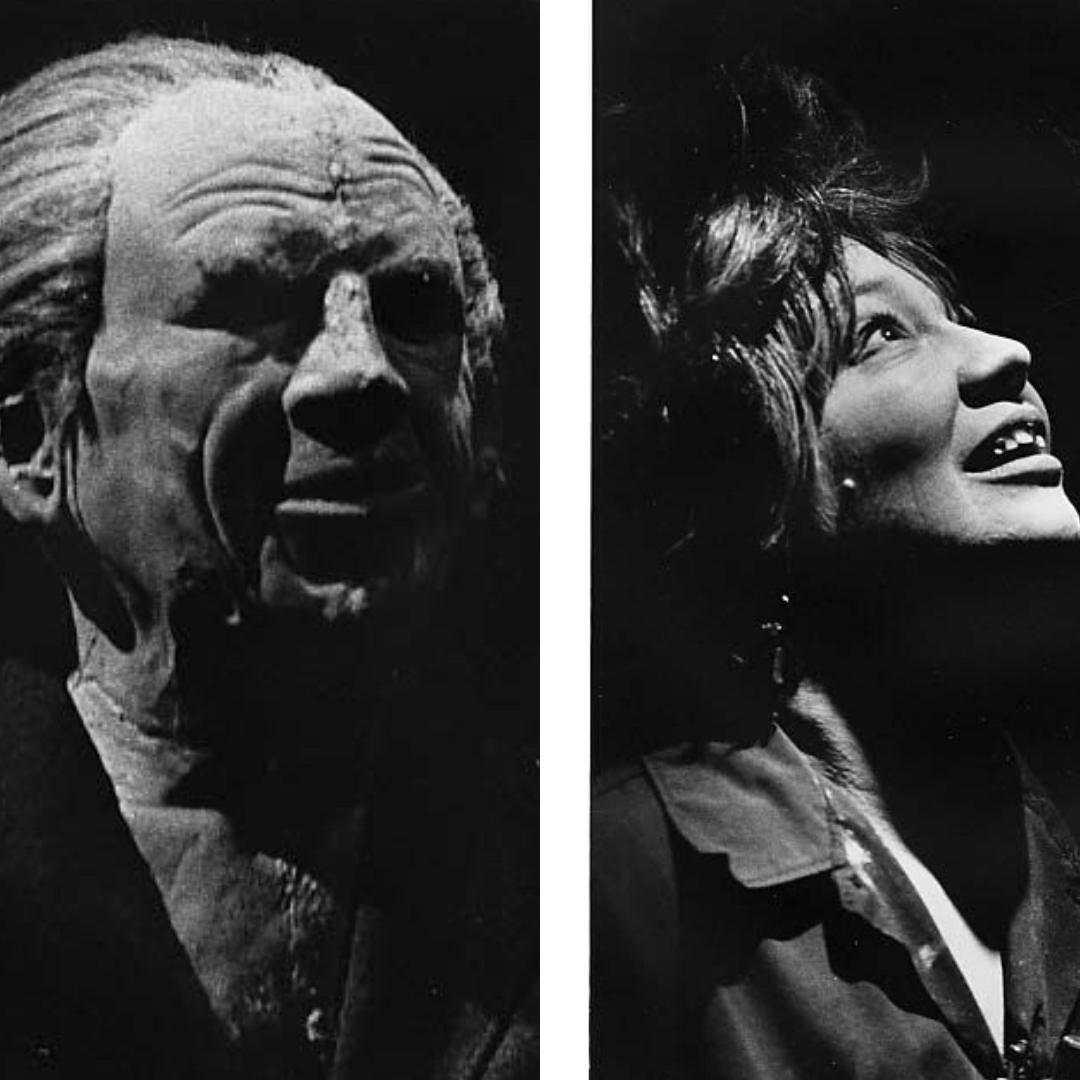

Maleczech is an almost disturbingly powerful actress. Her voice is even, her gestures meticulous and understated, but under the lights she becomes a witch harboring secret, unpredictable forces. Her wide, alert face expresses an inscrutable calm.

In Hajj, when she purrs into the telephone, “I’ll pay you the money, man, I’m not trying to rip you off,” she projects easygoing humor, stifled sorrow, and a frightening, exotic quality all at once. And, sitting silently in front of the mirrors, she really does make you think that she is summoning from the depths of her soul the images that appear on the glass. With such an electrifying yet evanescent presence at its core, Hajj never becomes a purely visual work or a purely verbal one, but remains stubbornly theatrical. It is a moment of primitive magic, a performance poem in which ‘the vehicle of time never moves at all.’ ”